By Ruth Steinhardt

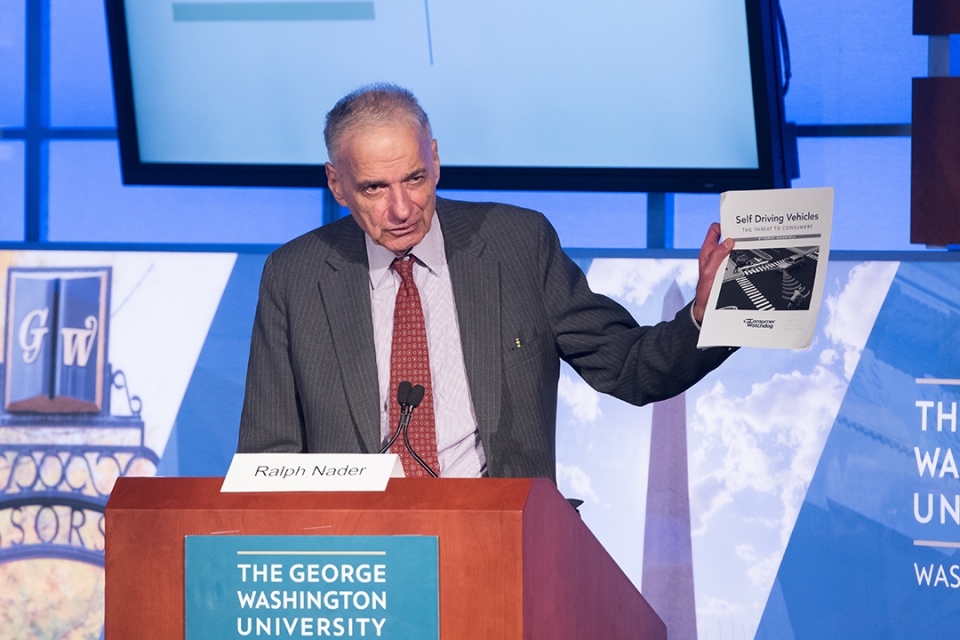

The excitement surrounding the advent of driverless cars obscures problems their rise will cause, consumer protection advocate and former presidential candidate Ralph Nader said at the George Washington University Law School.

"You see hubris, you see hoaxes, you see hype, you see hope and you see hysteria, technical hysteria, motivated by images of massive sales," Mr. Nader said, speaking at a symposium on the legal landscape of driverless cars.

Mr. Nader was a mid-day speaker at the all-day symposium, hosted last Wednesday by GW Law's Innovation and Internet Initiative Program.

The day also featured four panels comprised of industry representatives, federal and state officials, legal experts and auto safety and workers' rights advocates: one on the testing phase of a driverless car rollout, one on the deployment phase, one on liability and insurance, and one on other issues like impact on workers, cyber security, privacy and antitrust.

The symposium presented a platform for debates over questions such as whether manufacturers should continue to be primarily responsible for self-certification of the safety of their driverless vehicles; can regulators strike a balance between protecting the public and stifling innovation; what new issues arise in determining liability for accidents involving driverless cars; and what roles should federal and state play in the process.

In the morning's opening session, Jonathan Weinberger of Auto Alliance gave an overview of what is meant by an autonomous vehicle. There are different levels of such automation, Mr. Weinberger said, many of which are already in widespread use. Driver assistance in steering or acceleration, for instance, is a form of "level one" automation.

Some problems, Mr. Weinberger said, were complex trade-offs. The rise of driverless cars is hoped, for instance, to lead to fewer car crashes—but that would mean fewer organ donors.

During his address, Mr. Nader said that despite the attention autonomous vehicles are receiving, they are not a simple replacement for existing automotive technology. The deployment of fully autonomous vehicles would require new investment not only in the cars themselves, he said, but also in the roads they drive on, the systems to which they connect and the regulatory framework that surrounds them.

"The genius of engineering progress is always to bend toward simplicity as much as possible," Mr. Nader said. "This bends toward mind-numbing complexity."

More efficient driverless vehicles already exist, he said, in the form of mass transit.

"Isn't that the most wonderful driverless vehicle?" he said. While a single driver operates a train, "everyone else is chatting, snoozing, reading the paper, checking their emails."

Mr. Nader said the narrowness of the national conversation around driverless vehicles is an "amazing" distraction from the possibilities that improved mass transit or new systems—for instance, a system of monorails—could offer.

"When you consider what we’re going to have to invest to replace the present system with so-called 'driverless vehicles,' what is needed to build a system of monorails is modest compared to that private and public investment," he said. "Who wants more cars, anyway?"

Driverless cars also will pose a major security risk, Mr. Nader said, since computer-savvy attackers could gain control over such a vehicle's steering, brakes and transmission.

"Automakers may call them self-driving cars, but hackers call them computers that travel over 100 miles an hour," Mr. Nader said, quoting a New York Times piece on car companies and cyber security.